| The king called the yogi to his court and asked for a blessing. The yogi said, “What have I to do with blessings? I teach people how to end their own suffering so they can bless themselves. Regardless, since you asked, here is my blessing: May your father die, then may you die, and then may your son die.”The king was furious over this invocation of death and ordered his guards to seize the yogi. They did so, but before they could carry him away to the dungeon one of the ministers thought it prudent to ask the yogi to explain. The yogi calmly said, “How wonderful it is when the old die before the young.”When human beings suffer, our innate impulse is to find the cause and implement remedies. History shows the multitude of solutions we have tried — social, political, economic, physical — have failed to ultimately solve our problems. This is because our problems aren’t based in the world, they are expressed in the world. In other words, our problems in the world are effects, and if we wish to remedy them we must deal with the causes. The causes in yoga are known as kleshas, obstructions.The originating obstruction, according to yoga philosophy, is based on a profound misunderstanding of our own identity and our purpose for being alive in this world. This confusion is called avidya, which literally means “a lack of wisdom.” Because wisdom in this context means knowing one’s own Self, the lack of wisdom denotes a failure to know one’s own true being. In modern parlance, to be unrealistic about one’s self is to be mentally ill. From the yogic perspective, our world is filled with people who suffer from the mental illness of avidya. As a result of mostly subconscious interpersonal agreements, we live in a social construct where avidya and its by-products — hurry, worry, fear, guilt, anger — are considered normal, even necessary. When we recognize the pervasiveness of avidya, we can appreciate why the world is filled with so much distress. Distress is inherent in avidya and its primary expression, asmita, ego, the false self. The ego is built on temporal physical and psychological ideas of identity. This is why it seems to take time to construct a personal identity, and why self-esteem is a process that needs constant attention and defense from the threat. When Self is denied or forgotten, the creation of ego results. The energy of identity has to go somewhere. If it is not directed into reality, it will be channeled into dreams. These dreams, when undertaken by a majority, quickly turn to nightmares. We can see this in our world as people struggle with their sense of identity-based on religion, nationality, politics, even gender. From the yogic view, you already have a divine identity that cannot change or be revoked. You are free to adopt roles based on this current life and your proclivities, but they have no more significance than the costumes you might wear on Halloween. Go ahead and have fun trick-or-treating, just don’t take it so seriously and remember, “It’s only a costume.” The reason there are so few treats and so many tricks in our modern world results from the dynamics by which the ego tries to make itself secure. These are called raga, and dvesha, literally, “attraction” and “repulsion.” To more adequately describe raga, we must understand selfish desires as deep-rooted, obsessive, even addictive. Dvesha conveys a repugnance bordering on hysteria, closer to a fervent hatred. Although it may seem innocent enough to prefer ice cream over pickles for dessert, on more substantive issues, raga-dvesha reveals a fanatical attachment to getting what we want and avoiding what we don’t want. The problem with the raga-dvesha approach to life is that it is a strategy bound to fail. There is never enough getting to satisfy. There is never enough avoidance to feel secure. Plus, each ego’s raga-dvesha dynamic is slightly different from the drives of other egos, invariably resulting in conflict over objects, relationships, and resources. In the world of egos, peace is impossible. This inconvenient truth might be depressing, but it is crucial we recognize the dynamic of the ego if we wish to really achieve peace. You can’t shake hands while subconscious impulses are causing you to make a fist. The culmination of the kleshas is abhinivesha, clinging. This is the futile attempt to find permanence in the ever-changing. We seek safety, security, and comfort, but we look in the wrong direction. There is nothing in the world of time that can give the timeless succor we so desperately want. Yet we continue to try, again and again. We are not sinful or malevolent, we are simply repeating the same mistake in different forms.The good news is that once we recognize we are mistaken, we can humbly dust off our pants and get to work on correcting our mistakes. The even better news is that correcting mistakes in this realm of cause takes less time and energy than it did to create them. And the even greater news is that the remedy is available everywhere, for everyone, always. The remedy to suffering is a medicine with two ingredients: jnana(wisdom) and bhakti (devotion). Wisdom is the process of self-reflection in which we choose to uncover our ignorant (avidya) and selfish (asmita) impulses of pursuing pleasure (raga) and avoiding pain (dvesha) in pursuit of security (abhinivesha). Bhakti is the process of loving and serving others. My current working definition of love is the willingness to join with another in his reality for the purpose of upliftment, with no ulterior motive other than the inherent joy of doing so. Under the influence of avidya, the sense of loss and isolation is so great we feel as if we are no one. Under the influence of asmita, we try desperately to be someone. Under the influence of love and devotion, we relax, as we enter into the reality of our divine nature, and experience the truth that we are present with everyone. We don’t lose ourselves by joining with others, instead, we forsake the pain of feeling like no one and the frenzy of trying to be someone. We settle into our Self; an identity that exists as part of the whole, instead of apart from the whole. Like a leaf on a tree, we sense our relationship with all the other leaves. Like a wave on the ocean, we rise and fall from the same source as all other waves. The fear of death is cited in the yoga literature as the supreme example of abhinivesha, clinging. Yet, if we can quietly look at the situation, to fear death is to fear the only stable truth of living in time and space. We will leave here. We are passing through. For this very reason, it behooves us to live with as much wisdom and love, and as much gusto, as we feel we are capable of. The reality of the death of parents, children, and self is not a curse, it is a blessing. |

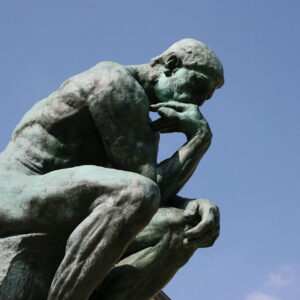

The Myth of ‘The Thinker’

In our modern age, we often imagine we are too sophisticated to believe in myths. We scoff at the beliefs of previous eras, when supposedly